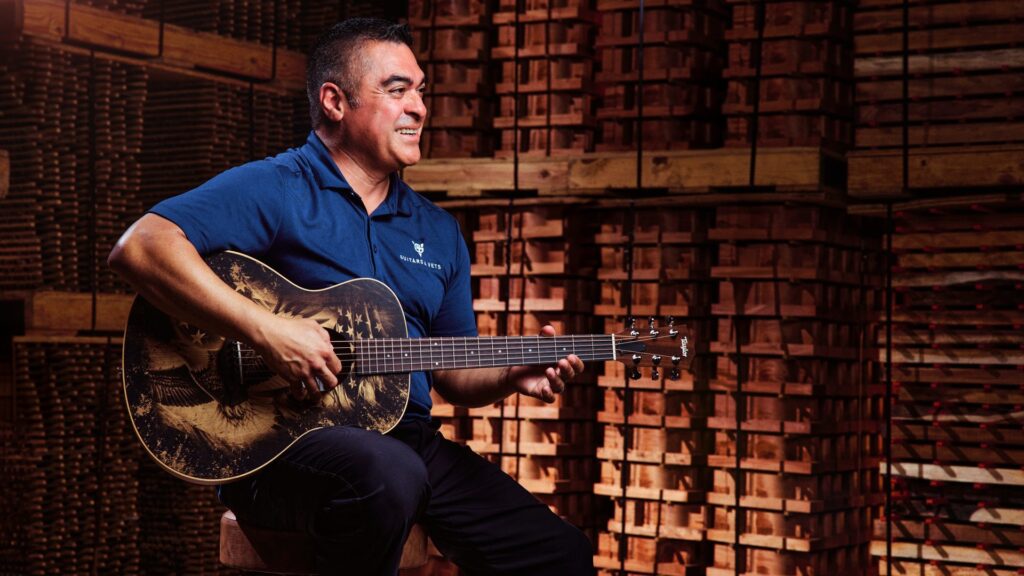

Ed. Note: We’re pleased to welcome Wayne Johnson, a Grammy-winning guitarist and Taylor Road Show product specialist, back to the pages of Wood&Steel as a regular contributor. In addition to writing instructional pieces, Wayne will also be presenting online video lessons, some as W&S companion pieces and others on a new lesson page we’ve set up on the Taylor website. The lesson page will encourage interaction between Taylor players and Wayne, and allow him to field questions and share additional guitar-playing tips.

If I were to ask you to play me a C major scale, what note would you start on? The logical answer, of course, is C. It’s the tonic, the home base, the reason the scale is named C. Now let me ask you this: Can you play me a C scale without starting on C? Or rather, can you play me the notes that belong to the C scale without starting on C? Why is this so difficult?

Well, as you may have read last issue in Shawn Persinger’s article, “The Irrational Fretboard,” the guitar fretboard is not logical. I can show a four-year-old the C scale on a piano, and within a few minutes he or she could play that scale up, down and randomly. It is completely visual. On a guitar, it would probably take that same four-year-old a couple of weeks to learn a C scale — and that’s just in one position. Unlike the piano, all fingering on the guitar changes as you go up the fretboard. Learning the C scale in seven positions (one position for each of the seven scale tones) requires that you learn seven different scale forms.

Because the guitar is so different in this respect, we resort to memorization to learn it. We practice the same thing over and over again until our fingers “get it.” The problem with muscle memory is that we play like we practice, and we play what we practice. If your entire guitar methodology is muscle memory, then your creative experience will be nil. How many times have you tried to play something that turned out to be much easier if you started somewhere else first? Hence, the C scale is easy, as long as you start on C!

Don’t get me wrong — memorization is a useful technique for learning how to play guitar. Because of it, some things are actually easier on guitar, such as transposition. You can take a song in the key of A and easily play it in B by thinking “up two frets” for everything. Try this on the piano! You’re not thinking about the harmonic relationships in order to play this song in B. You’re using memorization skills. Well, I’m here to tell you that this is all good. We need to take advantage of the easier elements in learning this instrument to make up for the more difficult ones.

My goal here is to show you a different type of visualization on the guitar, one that will help you learn and recognize shapes, groupings, intervals and symmetry. Through this visualization process and the practicing of scales and passages in a more linear (horizontal) manner, and by concentrating on single-string and random scale-note practice, you’ll start to wean yourself off many of the memorization crutches that block your creative expression. This process will not only help train your ear, it will also greatly improve your melodic development.

A couple of notes before we dive in. First, this is a fretboard lesson (left hand for most), so you may use your picking hand in any manner you wish — picks or fingers. Also, I’d like to say a few words about positions and scale forms. Basically, a position number is the fret number where your index (first) finger (on your fretboard hand) rests at any given time. For example, in position 5, your index finger would fall along the fifth fret. Following naturally up the fretboard, your second finger rests on the sixth fret, third finger on the seventh fret and fourth finger on the eighth fret. The only alteration to this formula is that your index finger might reach one fret below its home position fret, and your fourth finger might reach above its home position fret at any time if needed, without it actually signifying a position change. These are just momentary stretches.

Scale form numbers have nothing to do with position numbers. Position numbers tell you what frets you’re going to be centered around, whereas scale form numbers tell you what shape you’re going to play, in that position. There are different methods of learning scale forms. I like the simplicity of using seven scale forms — one for each degree of the scale. This simply means that in scale form 5, for instance, your lowest note or first finger would be starting on the fifth note of the scale. Scale form 3 would start on the third note of the scale…and so on. This will become more obvious as we get into it more. Now, let’s get started!

Fig. 1 is the C major scale in open position. It is in open position because it incorporates open (unfretted) strings to complete the scale. In open position, your first finger would be located over the nut, which we’ll call fret 0. Fret 0, or open E, is the third note of the C scale, so this will be scale form 3. Notice that the inside one-octave C scale is darkened. The orange notes are extensions of the C scale below and above the inside one-octave scale. The tonic or C notes have a circle around them. All of these notes are part of the C major scale. Fig. 1A shows how you probably learned to practice this inside C scale over and over again. Now, using Fig. 1,

start from the lowest note (open E, sixth string) and work your way through both the scale extensions and the inside one-octave scale, all the way to the last note of this open position — third finger, third fret, first string. It won’t really sound like a C major scale because you are starting on an E, but this is exactly my point. You can start on any of these notes and you will still be playing a C scale. The notes of the C scale do not have to be played in order or even start on the tonic (C) to be considered a C scale.

Now let’s look at the visual symmetry within this scale form. First, your sixth string and first string are both E, so you know the notes are going to fall on the same frets. So, on both strings you have notes on frets open (0), 1 and 3. It just so happens that the second string has the exact same fret locations. This makes three identical string-fretting patterns! Strings 4 and 5 have symmetry in that the fret locations are also identical: 0, 2 and 3. This leaves only one string with no symmetrical partner. Can you see how this breaks up the chronological order of practicing? Without even knowing the notes, on strings 1, 2 and 6 you play the same locations: frets 0, 1 and 3. There is no muscle memory involved because you have now learned the symmetry — the shape. All you have to do is play those identical frets and strings randomly and you are halfway there. Do the same for strings 4 and 5, only on frets 0, 2 and 3. Now you have groupings of three strings and two strings that are symmetrical, with only the third string alone, which you only play open and at the second fret. Once you learn these locations, you can easily play the scale in any order without the limitations of muscle memory.

Now let’s look at Fig. 2. This is the C scale in position 2. Since your first finger starts on the first fret, which is F, the fourth note of the C scale, it is scale form 4. Notice its shape and how different it is from scale form 3. Also, notice that even though your index finger’s home fret is position 2, this scale form starts with a lower fret stretch down to the first fret. The inside one-octave scale here (darkened) starts with your second finger on the fifth string, third fret. This means your index (1) finger is located over the second fret. Fig. 2A is how you would typically learn this C scale position. The orange notes in Fig. 2 are the extension of the inside one-octave scale below and above. Let’s start with the lowest note in this position (F) on the sixth string, first fret and work our way up to the top note (A) on the first string, fifth fret. These are all the notes of the C major scale in position 2. Now let’s do the same thing we did in Fig. 1. Look for recognizable shapes and symmetry. We have symmetry on strings 1 and 6, while strings 4 and 5 have their own. These two pairs of symmetrical strings will make it easier to visualize in order to learn, just like the open position. In this position, strings 2 and 3 are unique to themselves, so there is no symmetry here. Practice these shapes like you did with the open position. On strings 1 and 6 the shape is frets 1, 3 and 5; on strings 4 and 5 the shape is frets 2, 3 and 5; string 3 is frets 2, 4 and 5; and string 2 is frets 3 and 5. Learn these locations symmetrically and in terms of shapes and you will start to see patterns that will allow you to learn and play these scale notes in random order.

An interesting exercise for both positions (with no guitar!) is to close your eyes and visualize the symmetrical shapes of these two positions and scale forms. Play air guitar to practice, putting your fingers on imaginary frets. Play the symmetrical string sets and unique string sets just like you would with a guitar, and then practice hitting locations randomly. If you have doubts, open your eyes and check the notation. “Playing” without a guitar is actually a great way to zero in on this learning process without any sonic distraction.

Now let’s combine positions open and 2 so that we hit all the C scale notes available up to the fifth fret. Fig. 3 illustrates this. Look at the symmetry with these combined positions. Strings 1, 2 and 6 are identical. Strings 4 and 5 are identical. String 3 is the only one that is unique. In order to practice these two positions combined, you will be moving your hand back and forth between the two. Practice the two groups of symmetrical strings separately until you can play any location randomly. Then combine the two groups. String 3 will be a separate study, but because it is only one string, it will take little time. Do the “eyes closed air guitar drill” with these combined positions. The goal is to develop total freedom in the playing of all the C scale notes up to the fifth fret.

You can do this “eyes closed” exercise anywhere, anytime. (Well, perhaps not while you’re driving!) By visualizing all the shapes and patterns in your mind, you will soon be able to play any combination of these notes with no muscle memory. You’ll be able to play the C scale horizontally, vertically, diagonally, randomly and in the typical, chronological scale progression.

This may seem like a lot to think about now, but it really isn’t. As with most learning processes, there is a bit of a system involved, but the ultimate goal here is to free you from the thinking process. With practice, eventually you will be able to bypass the interfering mind to engage your creative process and let melody flow from your heart and soul to your fingers.

Of course, you’ll probably want to learn many more scales this way, but after you get the process down, it becomes much easier. By the way, in case you didn’t realize it, you didn’t just learn the C scale only. You just learned seven different scales, one for every chord or mode that is built on each of the seven notes of the C scale! Do I sense the glow of a light bulb above your head? We’ll attack that subject in a later lesson. For now, just focus on the C scale. And don’t feel like you have to replace your entire approach to the guitar now. Simply add this to your arsenal, and let things happen as they will.

One final thought. Since learning note locations in this manner can be a bit tedious, let me share one more practice example that should prove to be a little more musically fulfilling. In Fig. 10, I use all the same C scale notes and locations from this lesson, but this time I outline the seven basic tonal areas (modes) that exist from the C scale in the form of three-note chords or triads. This is actually being played in a scale-related fashion, but through the intervallic structure of the chords it makes for a melodic and harmonic little journey.

For now, I hope you can see how freeing yourself from typical scale practicing can open a huge door to melodic development and improvisation. One day as you’re playing, something unique will fly from your fingers, and you’ll say, “Wow, that was cool. How’d I do that? What was that?” That, my friend, is the sound of “breaking the mold.” Until next time, have fun.

More on Practicing the C Scale

As you practice all the C scale notes up to the fifth fret as shown in Fig. 3, you might find yourself questioning the tonality, especially as you start to play more randomly. I find it very useful to occasionally play a C chord to remind your ear of this home base. This way, for instance, after you play a C chord, the low open E will sound like the third of the C scale and not the root of an E home-based harmony.

As you get better at playing scale notes more randomly, you’ll find that something interesting happens — you start to train your ear as well. Before long you’ll be learning the intervals that you are playing and be able to anticipate the sound of the note you are about to play. This will help you shape your melodic development.

Know Your Notes

Do you know what notes you’re playing? It’s easy to look at a dot on a fretboard figure and play that note. Tab is very helpful in the same manner. Although you can do this whole lesson without knowing the actual notes, I encourage you to learn what notes you are playing. You don’t have to be concerned with reading notation if that’s not your thing, but believe me, knowing your notes will help you down the line in so many ways.

As you practice randomly playing different C scale notes, try saying the note out loud as you play it. For extra ear training, try singing the pitch as you say and play the note. Randomly, this can be fun and it’s a great workout. At first your vocal may come out a little after you hear the pitch, but as you develop this ability, you’ll be able to do it simultaneously. If you have trouble finding the notes in your voice box, play the same random interval two or three times until you hit it. Learning to sing these intervals is invaluable! Playing the notes in chronological order does no good because it’s just the first seven letters of our alphabet repeated in the same order.

Get Vertical

There are many approaches to this visualization process. I think that learning the guitar in a linear manner like this is a great way to break up our typical vertical position, muscle memory approach. That said, you can also visualize these positions and find symmetry in a vertical manner. As you look at Fig. 3 again, observe frets 0, 3 and 5. With the exception of the third string, third fret, every one of these notes is played straight up or down vertically. You could use this as well while you’re visualizing and come up with some totally unique intervals and exercises to further aid you in “nailing” the C scale.