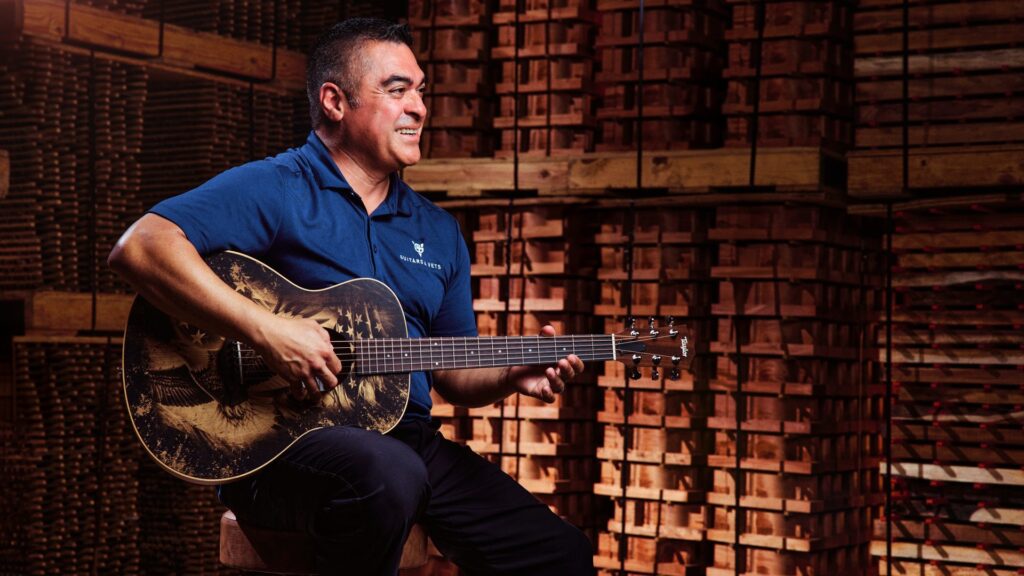

The first time I saw an acoustic guitar that spoke to me was in 1998, as I was looking through a Taylor Guitars catalog. It was a gorgeous 614ce. The shape of the guitar—a Grand Auditorium—was compelling, the headstock looked cool, and the blonde, beautifully figured maple back and sides really set it apart from the aesthetics of other acoustic guitars. That random find from a photo in a catalog sparked what became my life’s work in the musical instrument industry, including a yearning to fully understand how acoustic guitar tone is created.

As I would come to learn, the types of guitar wood selected play an important role in flavoring a guitar’s voice. Another important factor is the way a guitar is braced internally. Guitar bracing refers to the arrangement of wooden struts that are glued to the underside of the top and back. The way the braces are shaped and positioned does two important things: provide structural support and orchestrate the vibration of those parts to shape the tonal response.

Maple’s History in Music

Maple has a rich history as a musical tonewood. It has been revered in the violin family of bowed instruments for centuries because of its sonic presence and the way it faithfully conveys the technique of the player. Maple would later migrate to guitars, but at a certain point around the mid-20th century, something was lost in translation, and maple flattop acoustic guitars suffered as a result of the standardized, factory-style approach to making acoustic guitars. By that time, rosewood and mahogany had become commonly used tonewoods for the backs and sides of acoustic guitars—a crossover influence from the woods used in the cabinet and furniture trade as more and more carpenters and cabinet makers started making guitars.

The problem was that guitar makers essentially applied the same bracing blueprints for mahogany or rosewood guitars to maple guitars and expected them to react like a rosewood or mahogany guitar would. But maple’s physical properties are different. Without getting too nerdy, it has to do with the degree of internal damping (guitar makers also describe this in terms of a wood’s velocity of sound), which refers to how the vibrational energy of the strings passes through the woods. Rosewood tends to have low internal damping (and a high velocity of sound), which produces a lively response with a lot of overtones. As a result, the bracing scheme for rosewood is typically designed to keep the overtone richness from getting out of control. Maple, by contrast, tends to have a higher level of internal damping (i.e., a somewhat slower velocity of sound), which produces a voice with less overtone complexity. So what happens when you use a bracing pattern designed for rosewood on maple? You add unnecessary restrictions to a wood that already has a naturally controlled response. Consequently, maple guitars became known for having less tonal complexity, less sustain, and a tendency toward a brighter, treble-prominent sound.

The good news is that for years those properties served guitar players well for certain applications. That perceived brightness and lack of overtone complexity made maple guitars a great choice for acoustic players fronting a large band with many instruments on stage (since the maple sound could cut through the other instruments to the front of the mix and be heard more clearly), or for players who liked to blaze lead guitar solos on an acoustic guitar. But for other acoustic players who craved a more versatile sound or who missed the sonic warmth and depth that other tonewoods could provide, maple left something to be desired.

How Taylor Changed Maple

This led Taylor master guitar designer Andy Powers to redesign our maple 600 Series back in 2015 to reveal more of maple’s natural musical strengths and make it more broadly appealing to players. It’s no surprise that he started by redesigning the bracing scheme for the maple back, which helped produce a warmer and stronger tonal response. He also customized the bracing patterns for each different body shape to highlight the unique tonal strengths of each. He brought nuanced refinements to other material components of the guitars as well, including the use of protein glue for the bracing, which enhances the transfer of energy to increase the tonal output.

Another unique design touch exclusive to the 600 Series is a special roasting process for the Sitka spruce tops called torrefaction. This helps accelerate the aging process to help the top vibrate more easily, producing a more resonant, played-in, responsive tone from the first guitar strum. The torrefaction process also gives the spruce a darker hue, almost akin to cedar, which conjures a more vintage aesthetic.

Overall, the revoicing of our maple 600 Series guitars yields more richness, responsiveness, volume and sustain, with brilliant clarity and pleasing sonic balance from the upper to lower register. For acoustic players who have typically steered clear of maple due to excessive brightness, a test-drive with these guitars is bound to change your opinion.

And visually, these maple/torrefied spruce guitars are also stunning. Since we apply one of the thinnest gloss finishes in the industry to our 600, 800 and 900 Series (the thinner coating allows the guitar to resonate more freely), the idea of adding a darker color to the maple was a challenge because that normally adds material thickness to the finish. But we devised a way to apply two coats of a hand-rubbed finish called Brown Sugar without adding to the finish thickness. The result is a deep, rich complexion that beautifully highlights the fiddleback figure in the maple sets we select for the series. As a result, the back and sides resemble the look of violin-family instruments. Other distinctive appointment details include a striped ebony headstock overlay and inlaid backstrap, ebony binding (with on-edge grained ivoroid for the purfling lines), a paua abalone rosette trimmed with ebony and grained ivoroid, and a grained ivoroid “Wings” fretboard inlay scheme.

There’s one other compelling reason to embrace maple: As a tonewood that’s native to North America, maple is a well-managed resource, and with continued planning, it can be cultivated and sourced in a responsible, sustainable way for generations to come.