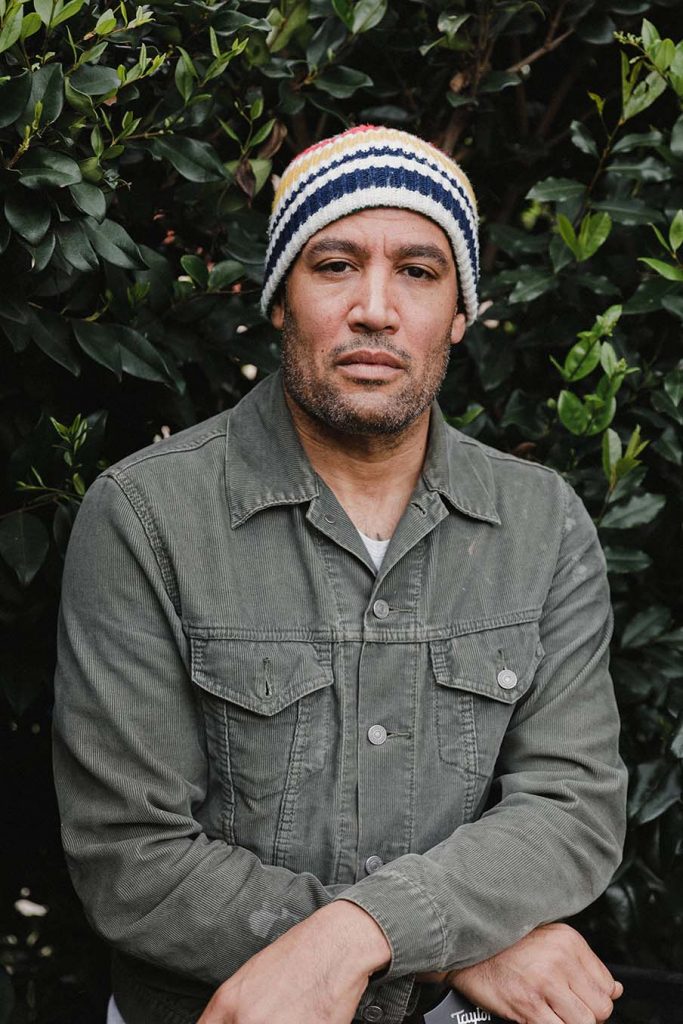

Editor’s Note: This interview was originally published in Wood&Steel Fall 2019. Find the whole issue here and explore Ben Harper’s artist page here.

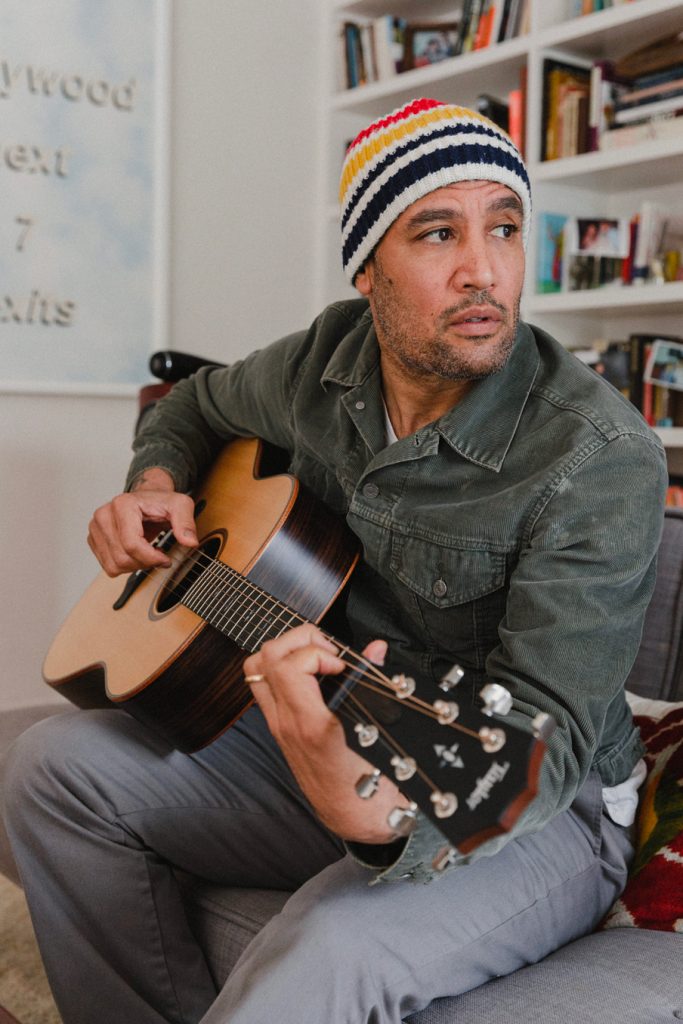

Ben Harper reflects on his eclectic musical journey, what he’s learned from his heroes, and why there’s no truth like the blues

Step through the doors of the Folk Music Center, located in the leafy Los Angeles suburb of Claremont, California, and you’ll find yourself surrounded by an assortment of exotic musical instruments and folk artifacts from around the world. Part store and part museum, the shop, located about 30 minutes east of downtown LA, has been dedicated to preserving international roots music culture since its founding in 1958 by Ben Harper’s maternal grandparents, Charles and Dorothy Chase. For years, Dorothy, a talented musician, taught guitar, banjo, dulcimer and autoharp. Charles repaired instruments and put the repair shop on the map as a go-to spot for the restoration of vintage instruments.

Over time the family store grew into a hub of the community. It was also a second home to Harper, who grew up working there, learning to play guitar and other instruments, and getting an immersive education in American roots music and the social issues that informed it.

Harper was exposed to guitars and other musical instruments most people will never see or hear, and learned to repair them. He also heard many of those instruments brought to life in the hands of the skilled musicians who visited the store — some unknown, others renowned, like world blues icon Taj Mahal, guitarist Ry Cooder, singer-songwriter Jackson Browne, and virtuosic multi-instrumentalist David Lindley, a regular customer who lived nearby and introduced a young Harper to the Weissenborn lap slide guitar he would later master.

Those years would stoke Harper’s desire to decode the mesmerizing guitar sounds he heard on blues records, like the syncopated fingerpicking techniques of Mississippi John Hurt and the slide work of Robert Johnson. Both the store and the family record collection would nurture Harper’s eclectic musical journey across the broad landscape of roots music. The genre-blending musical exploits of his 30-year career, spanning 14 studio albums, draw deeply from his knowledge of blues, folk, gospel, soul, funk, reggae, rock, hip-hop and other musical connective tissue. Wherever Harper’s musical instincts have led him, his songs have tapped into the essence of a great folk, blues or country song: They come from the soul, tell a story, and empathize with the struggles and hopes of the human experience.

The breadth of Harper’s catalog reveals him to be a tireless musical explorer, and no matter what genres his songs inhabit, they always resonate with deep conviction and soulful humanity. He’s done the work of absorbing — and often seeking out — his influences and putting in the time to carefully hone his own musical point of view. And it’s a process that’s ever-evolving, which is why one of the key attributes he says he looks for in a guitar is whether he can grow with it.

At this stage of his career, Harper has pretty much done it all — he’s been a guitar magazine cover boy; he’s sold scads of records and played stadiums with his bands the Innocent Criminals and Relentless7; he’s won multiple Grammy Awards; he’s worked with many of his musical heroes, including Taj Mahal, reggae/R&B kings Toots & the Maytals, gospel gurus The Blind Boys of Alabama and Mavis Staples (he wrote and produced Staples’ latest record, We Get By), and blues harmonica legend Charlie Musselwhite (with whom he made two critically acclaimed records). He’s rocked out with longtime friends and peers Eddie Vedder and Pearl Jam. He was among the invitees who performed a tribute to Bruce Springsteen as part of the prestigious Kennedy Center Honors. He and his mother, Ellen, even made a beautiful folk record, 2014’s Childhood Home, which showcased her talents as a songwriter and singer. Yet for all his musical successes, he says he has managed to stay grounded by his failures along the way.

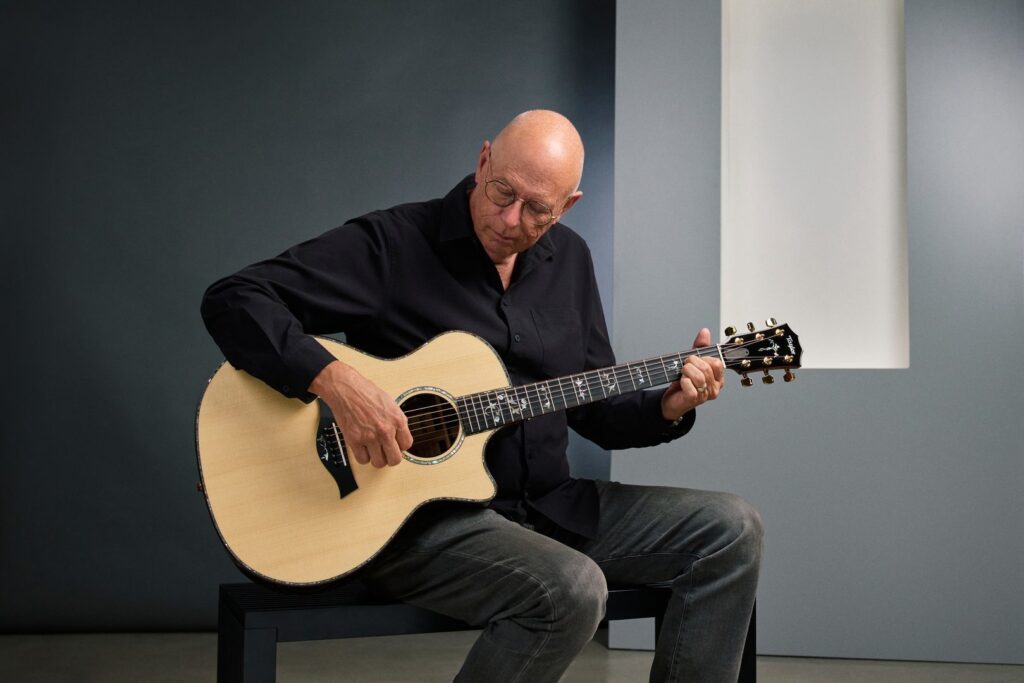

Harper connected with Taylor last year after finding a rosewood/spruce 810 he liked in a music store. He and Director of Artist Relations Tim Godwin already knew each other but hadn’t been in touch in a while, and as they caught up, Godwin suggested that Harper might like the Grand Pacific guitars we were developing. We sent him a couple of prototypes, and Harper felt a musical connection — the feel, the sound, and the new avenue of expression they offered.

The conversation continued, and a few months ago, we met up with Harper in Claremont to shoot some video with him both at his home and in his family’s music store, where he talked about a range of topics: his musical influences, his relationship with guitars, how listening to records inspires his creative process, and the parallels between the music business and another passion of his, skateboarding. We encourage you to check out those interview segments, which you’ll find at taylorguitars.com/artists. In early October we followed up with another conversation via email, when Harper was fresh off a string of tour dates with the Innocent Criminals. He’d had an opportunity to play some shows with his two rosewood Grand Pacific 717 guitars (he also owns a 517), so we thought we’d check in with him on his impressions of the guitars.

Your family’s music store seems like a special place. Can you paint a picture of the kind of environment your grandparents set out to create and what it meant for you to be immersed in that growing up?

My grandparents opened the Folk Music Center with financial help from my maternal great-grandparents Albert and Bessie Udin. Up until that point, my grandmother had been teaching guitar in the living room of their family home, and my grandfather had been repairing her students’ instruments in the basement. After a couple of years, it was taking over the entire house, so they decided to open a music store. They rented the small back storage room of a real estate agency. The owner of the building told my grandfather they’d never make a go of it in music retail, so they could rent it for cheap. The early ’60s folk boom happened, and before long, there were way more people coming in for guitars than houses. The real estate agency complained, and they soon had to find a larger space. I realized, even as a teenager, that music and instruments may have been the currency, but social progress and politics were the business. Literature, poetry and art were the language. I wish I could converse with my grandparents today. Every day in that environment was a cacophonous symphony from the minute the door opened at 9:30 until it closed at 5:30. Not only was it my home, but it was home to every artist who cared to walk through the doors — David Lindley, Chris Darrow, Jackson Browne, Taj Mahal, Leonard Cohen, Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee…the list is just so long.

I’ve heard you say that the family store was largely responsible for popularizing the term “world music.”

Customers would often comment that coming to the Folk Music Center was like taking a musical journey around the world. We were one of the first places that housed music and instruments from all over the planet. The term “world music” was coined in the ’60s, but at the Claremont Folk Music Center it was not a genre or catchphrase, it was a way of life.

Was there a particular artist or record or experience that first inspired you to play guitar?

Hearing Mississippi John Hurt for the first time did it for me. My grandmother played one of his records, and I asked her who “they” were. I was sure there were two guitar players. She assured me it was one man doing all the guitar playing and singing at the same time. Right then and there I knew for myself there was nothing on the planet that was going to be better than that.

How did you learn to play different styles, from acoustic fingerpicking to slide? Your mom? Other players who showed you things in the store? Or was it simply your own obsessive drive to figure out how the players that captivated you did what they did?

I studied and obsessed over the music that moved me. In my early twenties I made it my life’s work to sit at the feet of as many legendary blues players that would take me in. Brownie McGhee, John Lee Hooker, Louis and Dave Myers, Blind Joe Hill, Taj Mahal, David Lindley, Chris Darrow. And the ones who had long since passed, like Robert Johnson, Blind Willie Johnson, Furry Lewis, Reverend Gary Davis (who was a friend of my family’s and played at the music store). I studied them as if my life depended on it. This music was so lonely yet hopeful, so desperate yet confident, I had to get close to it and stay close. I looked at the world as clearly as I could at age 20, and nothing made as much sense to me as the blues. I took all that and applied it to my own material that I was writing at the time, filtered it through my own instincts, and that’s what ended up being my first album on Virgin Records, Welcome to the Cruel World.

I understand that David Lindley, who lived nearby and was a regular at the store, first introduced you to the Weissenborn. What about that instrument spoke to you?

Growing up in an eclectic music store, I developed a recognition of sonic and tonal uniqueness at a young age, so as a kid, I knew the Weissenborn sounded special even before I heard anyone play it professionally. But when David would come in, sit down and play the Weissenborn (which to this day is a regular occurrence), everybody in the store would immediately stop whatever they were doing to listen and end up slack-jawed, barely breathing while marveling at his playing and sound. For me it was the sonic equivalent of watching Michelangelo sculpt the Pietà.

How old were you when you knew you wanted to make music for a living? And because of the environment in which you grew up, did being a professional musician naturally seem like an attainable profession?

I never knew it was something I wanted to do for a living. I simply never thought it possible.

I was surrounded by extraordinary world-class musicians, humble working-class heroes whose names you won’t know, and many of them don’t want you to know it. They all had their hearts broken beyond repair by music, or more so by the music business. But business be damned, they did and still do it anyway, because we have to. That’s the school I’m from. When I was in my early 20s, Taj Mahal saw me play and brought me on tour with him to play lap steel in his band as well as to do some writing and recording with him. That was the first time I was paid real money to make music, and once that happened, once I had a glimpse of that as reality, it was over, there was no going backwards, there was no backup plan — matter of fact, there was no plan. I just knew I had to find a way to either survive by making music, or discipline myself to live so very simply, so that I could afford to make music the driving force in my life above all else.

And something else happened. Early on I passed through Nashville on my way back from playing Austin City Limits with Taj, and I made a point of going into Gruhn Guitars. This would’ve been 1992 or ’93. I went in, grabbed an acoustic lap steel off the wall, sat down and started playing. I looked up and saw a man with a massive snake around his shoulders. It was George Gruhn! He was so kind to me in regard to my playing, and in the many ways he wanted to support me. This stood out to me as a signpost that I might be able to get somewhere.

What did you learn being out on tour with Taj?

Touring with Taj was the single greatest moment in my creative life, on par with getting my own first record deal. Taj is the keeper of the flame, and has one-of-a-kind depth and a wealth of firsthand knowledge of the music that is most important to me. His musical instruction and guitar tutorials, as well as [his knowledge of] how to stay true to one’s creative visions, were exactly what I needed at that exact moment for me to take a next step, if there even was a next step. Taj revealed to me a world I could’ve barely dreamt of up until that point.

“The blues was so lonely yet hopeful, so desperate yet confident, I had to get close to it and stay close.”

People might not know that you’re also a skilled luthier and repaired instruments at the store. How did your understanding of how instruments were made impact your relationship with them?

I grew up learning to repair instruments, and in my late teens apprenticed with the late, great Jack Willock. Jack worked for Gibson in Kalamazoo, Michigan, through the late ’30s and early ’40s. Becoming friends and apprenticing with him are some of the best times and memories for me. The cats who would drop into his shop to have him work on their instruments were wild! One day it would be John Collins, the next day Howard Roberts, or Al Viola. Crazy! It has definitely impacted my relationship with guitars, knowing them inside and out. However, I rarely work on my own instruments. It’s the theory of the doctor not having himself as a patient, but sometimes I just can’t resist.

Social justice has been a strong through-line of your music throughout your career. I imagine this naturally resonated with you because of your family values and your immersion into the stories and messages in blues, folk, reggae and soul music. Do any particular experiences stick out as catalysts (for example, seeing Bob Marley perform when you were a kid), showing you the power of music to amplify these themes to the world?

Social justice was a major part of my upbringing, so it’s always been instinctual for me to represent that musically. Seeing Bob Marley at a young age definitely spoke to me as to how deeply that could resonate, and I was also raised with a healthy dose of Joe Hill, Woodie Guthrie and Pete Seeger. Those voices solidified how important and inextricably linked music and social justice could be.

When you were 20 you spent time in Chicago hanging some of the old blues players — people like Brownie McGhee and one of the members of the Aces. It’s obvious that you have great respect for their music and stories. Why was it important for you to seek them out? What sort of truths were you after?

There’s no truth like the blues. I felt it to be priceless that these older cats would let me spend time with them. I was just a 20-year-old kid who deeply loved and lived their music. They were all so gracious with me, and this was well before I had released a record. They wanted nothing from me, and good thing because I had nothing to give them other than wide-eyed enthusiasm.

They literally took me in. Louis Meyers from the Four Aces let me stay with him in his apartment! Winter, South Chicago. Wild.

Along similar lines, you have a rich track record of working with some of the legends of folk, blues and gospel. Besides Taj Mahal, you’ve collaborated with The Blind Boys of Alabama, Charlie Musselwhite, and Mavis Staples. Can you talk about the unique musical connection you have with each of those artists?

The Blind Boys of Alabama record [2004’s There Will Be a Light] recalibrated my entire trajectory. I was coming off two of the bestselling records of my career to that point (Burn to Shine, and Diamonds on the Inside), and it was naturally expected of me to follow it up with something that could build on that commercial success. It was at that time that the opportunity presented itself for me to work with The Blind Boys. Three of the five original members of the group were still alive. They were old, but their singing was stronger than ever, and I knew the opportunity wouldn’t come around again. I felt a sense of urgency, as if there was no choice but to do drop everything and make that record.

Working with Charlie Musselwhite is life-affirming. A rare and exciting experience, one that is still being lived and written every day. My entire adult life has somehow been aimed at collaborating with Charlie, and we have a lot of work still to be done.

Mavis is the sister I always wanted. She and I are like brisket and bread, a coat and top hat, Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen. I still wake up every day and am overwhelmed with gratitude and appreciation for having the chance to know her and to collaborate with her.

Anyone (living) come to mind who you’d love to collaborate with but haven’t had a chance to yet?

Bill Withers, Bob Dylan, Alison Krauss Paul Simon, Chuck D.

Not many artists can say they cut a record with their mom. The record you made with your mom (2014’s Childhood Home) is a beautiful collection of folk-flavored songs, and showcase your mom’s vocal and songwriting chops, not to mention sweet vocal harmonies between the two of you. One thing that impressed me was that it really felt like a genuine 50/50 collaboration — your mom is the real deal. What was the most satisfying part about making that record?

Thank you. It was a 50/50 collaboration. The most satisfying part above all was that we were able to actually accomplish it after talking about it for so many years. Another very satisfying aspect of it for me is how it will always be there for my kids and their kids and so on down the line. A sonic family heirloom.

“The Grand Pacific guitars seem to resonate even when not being played.”

In one of your previous conversations, you said: “A lot of writing is just about interpreting silence with as much soul and soulfulness as you can.” What does soulfulness mean to you, and is that something that anyone can learn to express, or do you either have it or you don’t?

That soulfulness for me is where experience and imagination meet. Where rules and structure fall away and are replaced by learning what can’t be taught.

You’ve mentioned three things that you consider when you pick up a new guitar: sound, feel and potential. You’ve obviously owned many different types of guitars over the years, so I’m curious about your initial impressions of these Grand Pacific guitars. And then speaking to the idea of potential, now that you’ve had the guitars for some time now, what have they been revealing to you musically, both at home and on stage?

The Grand Pacific guitars seem to resonate even when not being played. My favorite instruments tend to do this. Also, when I’m doing something else non-music-related, I tend to find myself thinking about playing them. On stage they have a massive full-bodied sound, and at home and in studio they have that intimate clarity that for me is a requirement with acoustic guitars.

You’ve got the mahogany/spruce 517 and rosewood/spruce 717. How would you compare the sonic personalities of each?

Rosewood and mahogany tend to favor their own set of frequency/wave forms and respond accordingly. More importantly, the 517 and the 717 are both sonically at the top of the food chain, so at this point it’s more about which one the song tonally requires.

What type of strings do you use on them? And when you play them, are you in standard tuning or do you use different alternate tunings?

I use D’Addario strings. Always. I do a lot in standard tuning as well as alternate tunings. If I’m writing in standard tuning but not finding what I want to say, I take that as a sign that it’s time to shake it up tuning-wise and explore.

Not only have you made records in different styles, but you seem to have a unique ability to connect with each instrument you play and find the best of what it has to offer. Do you sometimes feel like an instrument tells you want it wants to say and you become the interpreter?

Instruments have personalities that are often more interesting and informative than people.

Sometimes the instrument leads the charge and you follow. It’s great when that’s happening because it’s often unchartered territory.

What has kept you grounded throughout the high and low points of your career?

Failure and fatherhood.

Having absorbed so much musical knowledge and experience from older established artists and collaborated with them, at this stage of your career, do you find yourself starting to become the “older established artist” that younger artists want to collaborate with? After all, you’ve become a next-generation torchbearer of American roots music.

Well, if that’s the case, I’m honored to be that, and yes, I have noticed this shift starting to happen. It’s cool to have that much road behind me and still to this day feel like it’s all brand-new and the best is yet to come.

Skateboarding is another passion of yours, so much so that when you recommitted yourself to it in your 30s, it sounds like you made your management a little nervous! How does the exhilaration of executing a move compare to the feeling of playing a great show?

Yeah, that definitely was an issue early on until everyone recognized my skill set, and even still it’s always high risk, but that’s what it’s gonna be. My dentist is a skater, and he needs his hands every bit as much as I do. More important than the connection between a good show and landing a skate trick is the correlation between falling off the board and humility. The best thing I’ve ever done is fall off a skateboard in public. I mean slam really hard. Skateboarding is by far the most humbling endeavor in my life. I owe a huge amount of my humility to skateboarding. Not the makes, but the falls. Don’t get me wrong, landing a skate move and playing a song well are nearly identical emotions for me. Those rare moments where you feel like you’re doing something you’re born to do with no compromise. But all the falls that it takes to earn the makes, all the shit you have to deal with to just sing your damn song, who you become out of that is what matters to me.