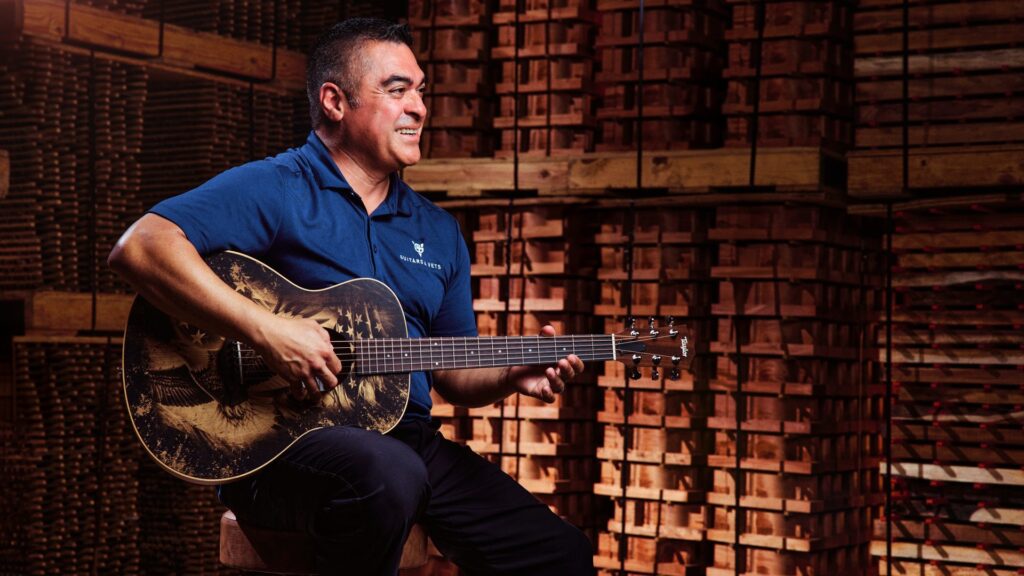

Ed. Note: In celebration of Taylor’s 50th anniversary, we’ve been rolling out a diverse array of commemorative limited-edition models all year. Of all the releases, the most exclusive offering is a pair of Presentation Series guitars boasting backs and sides of venerable Brazilian rosewood. The guitars will feature an Engelmann spruce top and be sold together with a Circa 74 amplifier specially crafted with a Honduran rosewood cabinet. We are only making two of these guitars because these are among the last sets of Brazilian rosewood Taylor has in its tonewood reserves. Given the wood’s rich heritage in the acoustic guitar world, we thought this would be a good opportunity for Taylor’s Director of Sustainability, Scott Paul, to shed light on Brazilian rosewood’s historical use and what eventually led to the industry’s transition away from it.

I first became aware of Taylor’s 50th Anniversary guitar collection sometime in 2023 during one of our recurring Wood Strategy meetings. Bob Taylor and Andy Powers (Taylor’s Chief Guitar Designer, President & CEO) were musing about creating a series of limited-edition guitars to commemorate the milestone year. Bob was thinking of updating some old Taylor classics — including early-era 800 Series dreadnought and jumbo guitars — while Andy wanted to build an assortment of guitars celebrating different tonewood species we’ve used over the years.

If you’re going to celebrate the historical use of guitar tonewoods, as Andy was considering, then you absolutely need to acknowledge the heritage of Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra). Its use dates back to the early 1800s when guitar making was in its infancy in Europe. At this time, Brazilian rosewood was well established as a popular high-grade furniture and cabinetry wood. The guitar, at the time considered an instrument of the commoner, tended to be built by carpenters and cabinet makers rather than makers from the instrument guild. Brazilian rosewood was plentiful in the marketplace, it worked well, and the tradition was born.

A Gradually Diminishing Supply

A few centuries later, Brazilian rosewood is not so plentiful. Population growth along the Brazilian coastline, over-exploitation and conversion of land to agriculture conspired to shrink the species’ native range to a sliver of what it once was. Its use is now highly regulated both domestically and within international trade.

When the idea of building a select few 50th Anniversary Brazilian rosewood guitars was proposed as a discussion point, initially I was taken aback. Taylor had long decided that we would no longer make such guitars. Bob and Andy felt that it wasn’t what we were about as a company anymore and that we didn’t want to buy more of what was essentially classified as an endangered species. I was happy when that decision was made. Remember, I’m the sustainability guy — you can take the boy out of Greenpeace, but you can’t take Greenpeace out of the boy. This said, by the time Wood Strategy was over that day, I had come around. I was good with it. I’ll explain why.

I’ve known Bob and Andy for a long time. My politics tend to be to the left of theirs. But ultimately, we agree on almost everything, as we each tend to bow to common sense. It turns out that Bob and Andy had a select few sets of Brazilian rosewood back and sides reserved in their personal stocks for a special occasion. It was now Taylor’s 50th anniversary. And you can’t build an assortment of guitars celebrating different tonewood species used over the years without giving a nod to Brazilian rosewood. (Bob made some guitars with Brazilian rosewood during Taylor’s early years.) With only a few sets left, if not now, when? I bowed to common sense. But I also thought I would take this opportunity to explain more about Brazilian rosewood’s CITES status and the history that preceded it.

The Curious Case of Brazilian Rosewood and The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

As some guitar players know, with limited exception, Brazilian rosewood cannot cross international borders due to the listing of the species, Dalbergia nigra, on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Frankly, there has always been a lot of confusion and misinformation about the listing, but I won’t go too far down the CITES rabbit hole here. I’ll simply stare over the edge and say that there are exceptions to every rule. An owner of a documented guitar made with pre-Convention Brazilian rosewood can apply for a one-time pass to travel internationally within a timebound period, and CITES does allow international travel in certain circumstances of specific non-commercial use, such as scientific research. Most importantly, every country enforces an Appendix I listing slightly differently. The United States, for example, needs to document that the wood was exported from Brazil before the species was listed in 1992, while the European Union requires that the wood is documented as having been in the European Union prior to the listing.

Setting CITES aside for a moment, I would like to put Brazilian rosewood into a little more historical context because…well, I love history, and as these two 50th Anniversary guitars could be among the last such guitars we make, this might be my last chance to talk about it.

Hundreds of Years of Use

The Portuguese landed off the coast of South America in 1500, when a fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral dropped anchor at what is today Porto Seguro on Brazil’s Atlantic Coast, an ecoregion that runs along the southeastern coastline of South America. At the time of European contact, the Atlantic Forest was vast, thought to stretch some 390,000 to 580,000 square miles (1,000,000 – 1,500,000 km2) and an unknown distance inland. It is this region where Dalbergia nigra grows on wet, damp land commonly found on rolling or mountainous terrain in fertile soil. It produces a beautiful and fragrant wood (hence the “rose” in the rosewood name) that was introduced to European markets and used in a variety of products, principally furniture and cabinetry.

The Atlantic Forest region was so big that for hundreds of years, the Brazilian rosewood tree was considered plentiful, but a few centuries of old-school logging, urbanization and land conversion to agriculture and cattle ranching can take its toll on even the mightiest of forests. In 1967, the Brazilian government reacted to the general demise of the Atlantic Forest, and Dalbergia nigra in particular, by banning log exports of Brazilian rosewood, though it continued to allow sawn wood to leave the country.

Sawn wood was largely brought into the international market by large wood brokers. In the U.S., they were based predominantly on the East and Gulf Coasts. There were few, if any, direct-to-manufacturer sales taking place. As it had been for a century, furniture and cabinet makers bought the lion’s share, and by 1970s and ’80s, “van conversion,” the specialized customization of van interiors, was in fashion, featuring Brazilian rosewood interior cabinetry. In fact, at least in California, the van conversion industry sourced more D. nigra than did musical instrument makers. Bob Taylor recalls in the early years that he would purchase his Brazilian rosewood from Browning Archery, as makers of fine bows traditionally used the species, too.

Finally, in 1992, a few months before Brazil was set to host the United Nations Earth Summit in Rio De Janeiro, the Brazilian government proposed the species for listing on Appendix I at the Eighth Conference of the Parties for CITES in Kyoto, Japan. It was a shrewd move for the host nation on the eve of what was to be the biggest environmental conference in history. Appendix I is CITES’ most restrictive category, a designation for species threatened with extinction. Up until this point, no notable commercially traded timber species had ever been listed before, let alone put on Appendix I. In the decades that followed, other species, such as Big-leaf mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), Pernambuco (Paubrasilia echinate) used for making bows for string instruments from the violin family, the so-called African mahogany (Khaya ivorensis), and the entire rosewood genus (Dalbergia) have been added to CITES but assigned the less restrictive CITES Appendix II. To date, Brazilian rosewood stands alone on Appendix I as a tree species that was listed as a result of commercial trade.

A Future Rooted in History

For many guitar players, Brazilian rosewood is a symbol of a bygone classic age of guitar building. To play one is to hear an echo from an era when the world was filled with old-growth trees. Do they sound better than other well-made guitars? The wood has undeniable sonic virtues, but ultimately, it’s subjective. At the risk of sacrilege, what flavor of ice cream is the best? (I like French vanilla, and no one can tell me any other is better.) Which wine is superior to all others? Yes, our 50th Anniversary Brazilian rosewood guitars do sound fantastic in the opinion of Andy and others here at Taylor, but so do other guitars made with other combinations of species.

Acoustic guitars are made of wood. Wood comes from trees, and trees come from the forest. When forests are well-managed, trees become a wonderfully renewable resource. However, poor management can lead to the depletion of tree species and the loss of biodiversity. So, the next time you press a guitar against your body, breathe in, and strum a chord, take a moment to appreciate the importance of forest conservation, restoration and responsible use.