Think you lack the innate talent of other players?

With enough desire and commitment, you can transform yourself into a “natural.”

When it comes to my guitar-playing ability, people often say to me, “You really have a gift. You’re a natural.” While I’ve learned to stop resenting this statement, I still feel compelled to explain that the only gift I may have is one of tenacity. I am in fact a very unnatural guitar player. I practiced a lot to get where I am today, and I continue to practice, study and refine what I do.

It is this lack of natural ability that makes me particularly sympathetic to students who struggle with their own playing, and who, despite their genuine desire, make only scant progress on their instruments. As a result, I have come up with several tips for players who are grappling with growth, have plateaued, or are simply looking for a new approach to the instrument. While these guidelines are not guaranteed to make you a better guitarist overnight, hopefully they will help you through the rough patches as you progress and give you a solid foundation for years to come. I’ll also debunk some myths that supposedly account for making a great guitarist.

The Truth Behind the Natural

Perhaps you know of a seemingly natural guitar player — someone who can play anything they want or figure out any song instantly. I had a good friend like this when I started learning, and it made me incredibly discouraged at first. Jeff was playing Carlos Santana songs, by ear, after playing the guitar for only a month! I’d been playing for over a year, could barely play a major scale without making a mistake, and the F chord was completely out of the question. So, how did Jeff do it? I found out much later that although Jeff had only been playing guitar briefly, he had been playing upright bass in the school orchestra for three years. I, on the other hand, had no musical training whatsoever. Jeff’s mother was quite musical and had played woodwinds since she was a teenager. As supportive as my parents were, and as much as my father loved bluegrass music, he would often say, “I can’t even play the bass on the radio.” Finally, Jeff played the guitar a lot. I was spending most of my time skateboarding and mostly just listening to guitar music.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, it’s easy to see why Jeff was such a fine player and I was so crummy. He simply played more than I did, took it a little more seriously, had training from a young age, and had a musical role model in the family. As good as Jeff was (and still is, even though he is now a pharmacist), he was not a natural. So, if you find yourself bemoaning the state of your talent, particularly if you are comparing yourself to someone else, get the full story. In all my years of teaching and surrounding myself with musicians, I have yet to find a great player who wasn’t, if not obsessive about practicing, at the very least highly habitual and persistent regarding their playing time.

When I have come across young players who I initially regarded as “naturals” with ostensibly boundless talent, I soon learned that they typically were excellent players only at what they liked to play, and at what came easily to them. It was difficult to convince them to practice something that was a challenge, something that lay outside their comfort zone or their innate ability. Instead, they would discount the challenge with a shrug and the dismissive statement, “I don’t want to play that.” Their natural talent was expressed only in a narrowly defined range.

Play to Remember

My “off the top of my head” repertoire includes several hundred pop/rock/country/jazz songs, a dozen classical pieces, and about 50 of my own compositions. Now, to some of you that might sound like a lot, but in the grand history of song that is a miniscule amount of music. While I do have enough memorized material to last me three or four sets, my recall is by no means flawless. I have studied every Beatles song in-depth, but I could only tell you something trivial about each tune. I could not play every one of them perfectly from memory. Perhaps this is obvious, but I, and most professionals, remember the songs we play the most. It’s the old cliché, “Use it or lose it.” There are in fact many mnemonics for remembering songs, but most of them require a pretty thorough understanding of theory. Chances are if you can’t recall the chord progression to a common jazz standard (Ex. 1), you will have even less luck remembering that the progression is just the circle of fourths starting on the ii chord. (This circle of fourths progression shows up in several songs, including: “Fly Me to the Moon,” “Take Five,” “My Favorite Things,” and even the Gloria Gaynor disco classic, “I Will Survive.”) If you really want to remember more songs, you just have to play them more often. And I don’t mean just practice them but play them in public, with friends and for an audience. Repetition will reinforce your memory and expand your repertoire.

That said, why do you actually need to memorize a piece? I play at least two dozen Bach compositions, but I have to sight-read every single one — there are far too many complex passages, unusual fingerings, and notes (Ex. 2) for casual playing. I am not planning a classical recital; I’m playing Bach for my own enjoyment. There is no shame in using sheet music for complex compositions. Have you ever seen an orchestra perform a symphony from memory? And I’ll let you in on another little secret: When I sight-read, I read the tab! While my notation sight-reading is passable, my tab reading is better than most classical musicians’ notation, so I usually start with the tablature first and use the notation for rhythmic fine-tuning.

Practice Routine. A regular exercise routine is certainly helpful, but if you are practicing aimlessly or without tracking your progress, your growth will be much slower and difficult to evaluate. Here are a few tips that will help you improve your guitar playing by leaps and bounds.

Keep a notebook. I can’t emphasize enough the importance of keeping a notebook of all the music you work on. While ultimately it is best if the book is organized into techniques, songs, genres, etc., simply having all your music in one place is of tremendous value. I strongly suggest keeping more than one. I have over three dozen three-ring binders filled with almost everything I have ever played, composed or taught over the course of 20 years.

Buy songbooks. Your ear is a fabulous tool, and judicious use of the Internet can be extremely useful, but I also encourage you to invest in some published music books. Though you will still find mistakes in books from even the finest publishers (legend has it Beethoven had nine proofreaders for his symphonies and they all found mistakes), the skill level of most professional transcribers is far beyond that of the average guitarist. A good book can highlight, among other things: proper fingerings, unusual chord voicings, altered tunings and subtle notational nuance unavailable from DIY tabs. For starters, I recommend “The Beatles Complete Chord Songbook” (Hal Leonard). While it contains no tabs, it does include every chord voicing and all the words, for every song they released. Seriously, if it was the only music book you owned, you’d be doing OK.

Keep a core list of songs you do know. Regardless of the number of songs you know, whether it’s 10 or 100, when put on the spot, many players become a deer in the headlights. Make a list and keep it in your guitar case or tape it to your instrument (à la McCartney’s Hofner bass). A quick glance at your personal repertoire of memorized songs should give you confidence and inspire you to play your best. Keep the list updated with your ever-increasing titles, and keep playing them whenever and wherever you can.

Teach. One of the surest ways to really prove whether you know what you are talking about is to teach it to someone else. You might think you know how to strum the intro to a folk-rock classic (Ex. 3) or the chorus of a hard rock staple (Ex. 4), but once you have to explain it in its simplest terms to someone who is looking to you for answers (and possibly paying for your time), you find out very quickly how much you really understand about rhythm guitar and how your right hand functions. You may also be lucky enough to have smart students who ask multifaceted questions that require you to go beyond your realm of expertise and become a bit more studious. It would be fair to say I’ve learned more as a teacher than I did as a student. Then again, as an “unnatural” guitarist, I don’t think I’ve ever stopped being a student, no matter how many players I’ve taught.

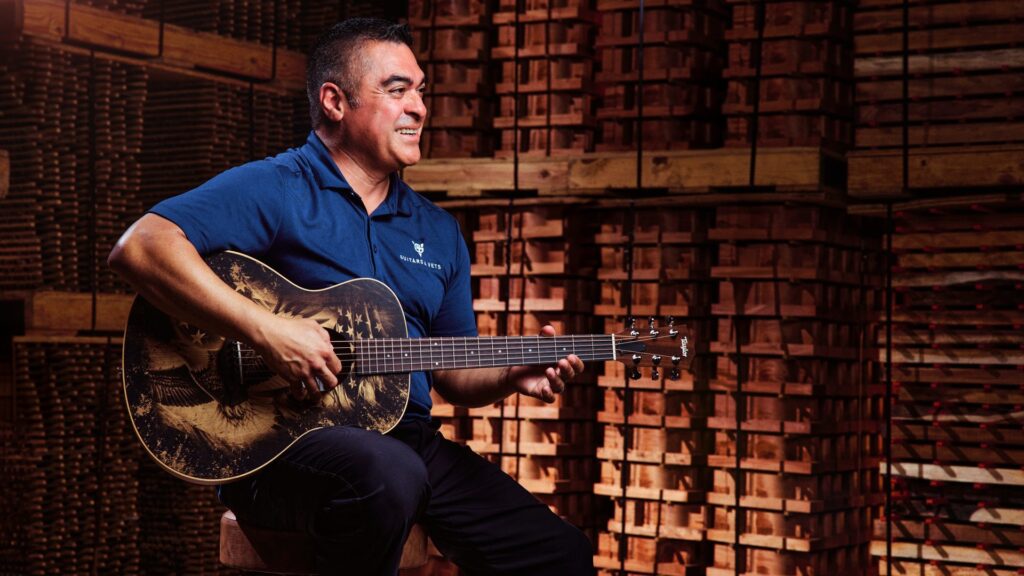

Shawn Persinger, a.k.a. Prester John, is a self-proclaimed “Modern/Primitive” guitarist who owns Taylor 410s and 310s. His latest CD, Desire for a Straight Line, with mandolinist David Miller, showcases a myriad of delightful musical paradoxes: complex but catchy; virtuosic yet affable; smart and whimsical.