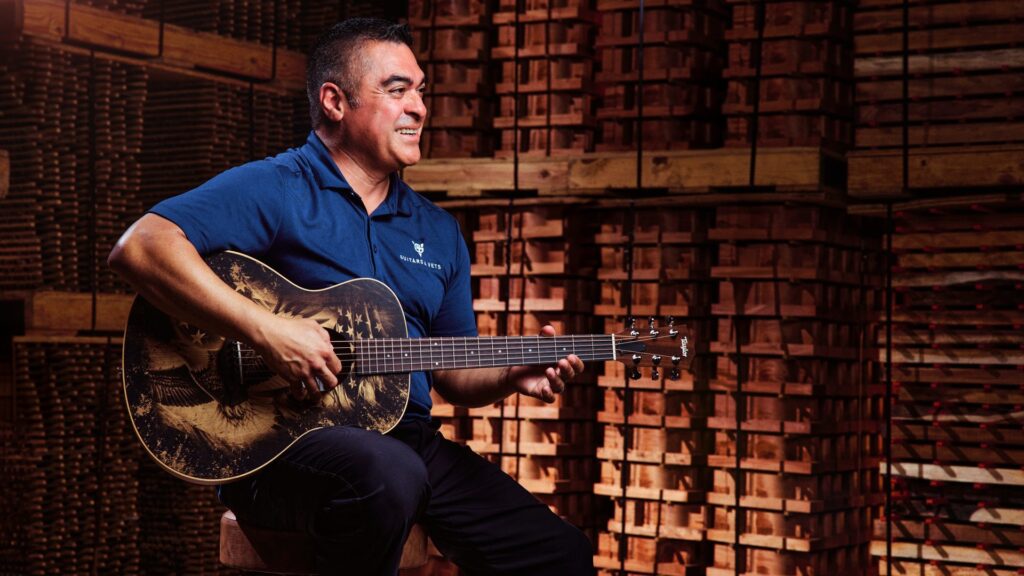

Alex Woodard wasn’t doing so well. It was 2008, and after nearly 15 years of plying his craft as a performing singer-songwriter, the modest record deal he’d scored had gone sour.

“It sounds like a typical musician complaint, but the label didn’t care,” he explains from his home in Leucadia, California, a coastal community in northern San Diego County. “They were supposed to be distributing the CD, but they weren’t really.”

To make matters worse, around the same time, Woodard’s beloved black Labrador retriever, Kona, his constant companion throughout his entire music career, succumbed to bone cancer.

The losses thrust Woodard into a period of intense self-reckoning. He understood the realities of the music business as well as anyone, and knew that he’d embraced a career path with no guarantees of success. As a survival mechanism early on he’d developed a mindset — a protective armor of sorts — that kept his music dreams insulated from the sometimes discouraging blows of the business. It allowed him to sustain the belief that success would eventually come if he stayed positive and focused on his craft amid the daily grind and inevitable setbacks. But his armor now had a chink in it. If anything, Kona’s passing was a painful sign that his long-term dream of “making it,” for years comfortably set in the open-ended future of “someday,” might in fact have an expiration date. He wondered whether he was actually gaining any ground on his dreams.

It wasn’t for lack of effort or creativity. His desire to connect with listeners through songs had prompted him to offer a unique incentive to anyone who pre-ordered his most recent CD: He would craft and record a song for each person based on whatever they asked him to write about. In the end he had more than a hundred takers, and he penned an individual song for every request.

“I recorded them right here at my kitchen table,” he says. “They weren’t necessarily fancy, but they also weren’t 30-second tunes; these were full-on songs.”

Woodard says the requests ran the gamut, from light-hearted topics to romantic themes to a few heartbreakers that left him with a lump in his throat when he read the requests. He discovered that he liked the creative process, which marked a departure from his largely self-reflective songwriting focus up to that point.

“For whatever reason, writing about other people’s stories came easier to me,” he says. “My writing had been me-centered for a long time in part because I didn’t have any mentors,” he says. “I probably didn’t think anyone would believe in me besides myself, so I wasn’t very open. I wasn’t looking for co-writing opportunities or anything collaborative. I kind of held everything tightly.”

Woodard had moved to Leucadia with Kona a few years earlier, after being based in Seattle for years, to reconnect with the ocean and his family up the coast in Long Beach, California. As he rekindled his passion for surfing and made new friends in the area, he found himself welcomed into a close-knit community of accomplished songwriters and musicians. He started getting invited to regular “family dinners” — potluck gatherings that inevitably ended with informal jam sessions. The group included some acclaimed talents — people like Switchfoot frontman Jon Foreman (814ce, 614ce, 514ce, GS6, GS5), Sean and Sara Watkins of Nickel Creek fame, award-winning tunesmith Jack Tempchin (“Take It Easy,” “Peaceful Easy Feeling,” “Slow Dancing”), vocalist Jordan Pundik from the pop-punk act New Found Glory, and even luthier/musician and soon-to-be Taylor employee Andy Powers.

Woodard’s new friends also got to know and love Kona, and later offered their support when she passed. Months later, Woodard was still in the midst of some soul-searching when, out of the blue, Emily’s letter arrived from across the country. Woodard didn’t know her, but his music had somehow found and connected with her. She wasn’t writing to commission a song, but simply to thank him for the ones she had heard.

“I think your songs are gifts,” she wrote. “Pieces of yourself used to help other people with their stories.”

In her letter Emily explained that her soul mate had passed away several years earlier and that each autumn — their favorite season — she would write him a letter to share her thoughts and memories, even though the letter would never be sent. But this year she had decided to send it to Woodard to share a piece of herself in gratitude for his music.

The letter touched him deeply, both because of its personal nature and because of the realization that his music had moved Emily. He showed it to Sean Watkins, who was also moved, and the two were inspired to write a song together based on the letter.

“In sharing her letter, Emily was being so giving that I wanted to share in the experience of writing a song about it with someone, and I’d never felt that way before,” Woodard reflects. “I’d always been holding on [to the process] really tightly. With Sean, we’d gotten to be friends, and he’s a great writer, so I thought, let’s just see what happens. And with that first song, ‘For the Sender,’ the collaborative thing came not only from the writing but from the singing, because when we recorded it, Sean sang it. That was the first time that I didn’t sing something I’d been involved with writing.”

The experience proved to be a creative catalyst for Woodard, enabling him to open himself up to a slowly unfolding collaborative journey with his new group of friends. It would lead to heartfelt letters from others, which in turn inspired more songs, eventually culminating with an album and a book, For the Sender (Hay House Publishing), in which Woodard poignantly chronicles his transformative experiences and the strong connections he made with others along the way.

“I would have never, ever thought I would be doing this,” he admits. “Writing a book — that was not on my radar. It wasn’t even a dream.”

Both the album’s song sequence and subsequently written book follow the natural progression of the songwriting process. After he and Sean recorded the song they’d written in response to Emily’s letter, Woodard sent it to Emily as a thank-you for sharing her letter. She replied with a beautiful note about how moved she was by the song, inspiring Woodard to write another song, “My Love Will Find You,” also based on her original letter. He enlisted standout singer-songwriter Molly Jenson and Jordan Pundik to sing it.

“That was the first time I’d really had nothing to do with it,” he says. “I mean, I wrote it, and I was recording them and producing the song, but I was completely out of the picture for the first time. So I let go of the performance side. I started to sense that I could get a much deeper connection if I just took myself out of it. I remember listening to Molly sing and thinking, why should I be singing this song? By then I realized I should just get the hell out of the way. Fortunately, in the years leading up to that, I had developed some skills for producing, arranging and recording. So I feel like everything kind of prepared me for this, for taking my hands off the wheel.”

Woodard continued to collaborate with his songwriting friends. Emily’s letter would inspire two more songs, one co-written with surfing buddy Jon Foreman, another written entirely by Foreman while he was out on tour and recorded when he was back in town.

In his book Woodard talks about the creative liberation he felt from writing about others’ stories and recording other people singing.

“In this new anonymity I begin to feel lighter and free, like a door has opened into a bright, airy room I’ve never seen, one that’s been in my house the whole time but I always just walked past,” he reflects.

Other random encounters led to more letters and, in turn, songs. Woodard and Foreman spent time playing guitars and hanging out with teens at a homeless youth shelter in Oceanside, California that Switchfoot has helped support for several years. After the director, Kim, sent a thank-you note to the two for sharing their time, Woodard wrote back to inquire what led her to do the work she does, and she replied with a heartfelt letter describing her own troubled youth living on the streets as a teenage addict, and of the people who helped her repair her self-image and rebuild her spirit. It would spawn three songs: a catchy, upbeat rocker written by Foreman, “Unbroken,” and two Woodard-penned tracks, “Love Began as a Whisper,” featuring the beautiful vocals of Molly Jenson, and a lively alt-country stomper, “The Right Words,” featuring Jordan Pundik on vocals.

Another letter came from Haiti. After a powerful earthquake ravaged the country early in 2010, Woodard had been asked to contribute a song for a benefit record. His tune, “Rescue,” ended up on the Web paired with some video footage of the relief efforts there, and a medic for Sean Penn’s foundation, Alison, saw it and e-mailed Woodard to thank him. After an e-mail exchange in which Woodard asked what the conditions were really like there, she forwarded him a letter she had written to her parents explaining both the overwhelming suffering and the incredible resilience of the people she had encountered. The letter inspired two more songs: “Act of God,” co-written with Jack Tempchin, and “Broken Wide Open,” written with Tempchin and Sara Watkins, who also adds a lovely, plaintive vocal.

The fourth letter came from Katelyn, the widow of a police officer who had been fatally shot in Oceanside, near Woodard’s town, a year and a half earlier, leaving Katelyn with a young son. It turned out that Woodard had met her prior to the shooting through a mutual friend. Katelyn had since remarried, and having heard through Sara Watkins that Woodard was writing songs based on letters, she wrote him one of her own. She explained that she and her husband had discussed the possibility of his being killed in the line of duty, and that he would want her to remarry and give her son a father. That conversation, she shared with Woodard, had enabled her to eventually move on.

The letter inspired Woodard and Sara Watkins to write the tune “From the Ashes.” Woodard comments in his book that this theme flows through the stories told in each of the four letters — as he puts it, “beautiful truths buried in the wreckage of tragedy.” Katelyn’s letter would inspire a pair of other songs: “Begun,” co-written with Jack Tempchin, about finishing what has been started, and “Hush,” a lullaby written for Katelyn’s young son and sung beautifully by another friend, Nena Anderson.

Even without the benefit of the greater context that illuminates the inspiration for the songs, the album’s tracks, which range from shimmering balladry to uplifting rock, boast a clarity, emotional depth and heartfelt melodic beauty. With the added knowledge of the letters and stories behind the songs, each track becomes even more powerful, revealing a deeper insight into the perspectives of the songwriters as they responded to a particular emotional theme.

Reflecting on the organic, homegrown nature of the project (including the recording process in his small home studio), Woodard says he was happy with the way the songs held together as an album, even though the creative approach varied for each song.

“I had to adjust to each person according to what their process is, but I’m pretty flexible with that kind of thing,” he explains. “I want the best for the song, and that means what’s best for the writer too.”

In the book, Woodard weaves his own personal stories from different periods of his life into his narrative as he relates to the stories in the letters. He realizes that he effectively did the same thing as he was writing the songs.

“The way that I write hasn’t really changed much,” he elaborates. “I just feel like the source changed. Instead of being somewhere deep in my gut, now the source was on these pages that people sent me. Those are the same thing, really. My story is coming out through those letters, even if I don’t think it is. My hopes and fears and dreams and all that stuff, it all comes out, even when I’m writing about other things.”

Woodard’s desire to share the songs with the letter writers led to another decision: to pay a surprise visit and play the tunes for them in person, often with some of his friends in tow. He, Sean and Molly traveled to Connecticut to play their songs for Emily. He, Jordan, Molly and Jon went to the homeless shelter and played their songs for Kim. He brought Nena, Sara and Jack to play for Katelyn and her son. And although Woodard couldn’t surprise Alison in Haiti due to the travel logistics, he flew there with his Big Baby to play for her and spent time in her world.

“I stayed in a tent in the living room of this burned-out house,” he recalls. “There was no water or electricity. Alison’s clinic was in pretty much the worst part of Port-au-Prince, called Cité Soleil, so that’s where we spent our time. She took me around the slums and we went into schools there. And despite the conditions, the kids were all dressed up in their uniforms — there was just this resilient spirit. I remember that probably the most. I went into these schools and played for kids, and there were just smiles all over the place. When I would start playing they would just stop what they were doing and look up at you and gather around. It was pretty powerful. You wish there was more that you could do. But sometimes that’s all you can do, go around and be present.”

As Woodard looks back on the extraordinary way the project unfolded and the impact it had on him both creatively and personally, he says he learned the value of letting go.

“Maybe your dream isn’t what you’re supposed to be doing,” he suggests. “And maybe what you’re supposed to be doing is something more beautiful than you could have ever imagined. We all know stories of people who go after their dream with blinders on and they get it, and then the real trouble starts. So for me it was a recalibration of sorts. There’s a great line from Bono in the U2 song ‘Beautiful Day’: ‘What you don’t have you don’t need it now.’ And I started looking at the world through that lens, like, what I have right now is what I need, and these big music dreams, I must not need them now; I’m probably supposed to be doing something else.

“And the ironic thing about that, which is in the book, is that once I let go of all those dreams, they started to happen, and that’s not for some kind of narrative convenience. That happened like it did. Great example: Shawn Mullins was a hero of mine in the songwriting world when I was cutting my teeth, and I tried to get on the road with him for something like eight years, but it ended up [not panning out]. So I kind of gave up and let it go. A year later he was in my living room through a

vehicle I could have never imagined — a fan of mine gave a CD to his tour manager, and the tour manager gave it to Shawn.”

Woodard’s book and CD were scheduled for release together in September (the CD is included in the book). At the time of our interview in June, he was working out the details with Hay House for a promotional tour. Because of the unique nature of the project as a book and album, there may be a mix of events — some speaking engagements with some solo performance of the songs, and possibly some shows with some of the musicians who participated in the making of the record. He’s done several gigs in the San Diego area, which made it easier for more of his busy friends to perform with him. The most recent show incorporated multimedia elements, including video footage from his visits with Emily, Kim, Alison and Katelyn, voiceover recordings of the letters from the writers, and live performance.

“No matter what form it takes, the start of the show will be the letters,” Woodard says. “We were talking about doing a Thanksgiving tour with everybody for a couple of weeks, but logistically it’s kind of a challenge. We might do just one show and record it, like a PBS special.

“I don’t know that it fits into a kind of traditional paradigm as far as putting an album out and touring goes, but I love it,” he says. “It’s a complete departure from what I’ve been doing for the last 10-15 years, and it’s so welcome. The model has just shifted so much that there isn’t a model now, but there’s still a lot of people out there who want to go see shows and listen to music.”

You can read more about Alex Woodard’s project and watch videos at www.forthesender.com and at www.alexwoodard.com.