Becoming a great guitar player requires serious dedication, but with busy lives, most of us don’t have enough time. Don’t be discouraged. Even minimal practice will lead to steady progress. When I meet new people in a social setting, inevitably I’m asked, “What do you do for a living?” I always reply, “I play guitar.” My answer is often met with a sigh and a confession of regret: “I wish I had learned an instrument.” I’d like to help anyone who shares this feeling to overcome it, because all you have to do is to start playing.

If you are reading this, then you probably already play guitar, but one of these scenarios is also possible: You’ve just begun to play and lack confidence in your ability; you recently purchased a guitar but don’t know how to embark on your playing journey; you are thinking about buying a guitar; or you have been playing for years but feel you’ve made very little progress. I’m familiar with all these perspectives because I receive e-mails on a daily basis from readers who share their personal experiences. I also have experienced all of these myself.

Great vs. OK

It is not easy to become a great guitar player. Becoming a master musician can take years and many, many hours of practice (the current thought regarding mastery of any skill is the “10,000 hours” theory set forth in Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers). But to become an “OK” guitar player actually does not require that much effort — a few months perhaps. And frankly, being OK is in many ways good enough! I don’t mean to sound like I’m encouraging anyone to shoot for mediocrity, but if your goal is to play music in addition to all the other responsibilities in your life (family, work, etc.), then begin modestly and realistically with small steps. Your commitment will be rewarded in a matter of months.

As a teacher I am very liberal regarding how much progress my students need to make. By this I mean I am not an instructor who dismisses pupils who don’t practice. I realize that many players are hobbyists with no desire to become professionals. While I always encourage my students to study as much as they can and to apply themselves wholeheartedly to the pursuit of music, when they do sit down to play I also understand the everyday demands on any individual’s time. Trust me, with two small children of my own, I sympathize with everyone’s time management challenges. So, when a fledgling guitarist shows up to a lesson and says, “I almost cancelled this week because I’ve barely practiced,” I say, “Not practicing is one of the best reasons to come to your lesson.” And those reasons are multifaceted. First, if you didn’t practice last week it is highly likely you won’t practice this coming week without some encouragement. Second, in our lesson I guarantee you will get to play guitar. Third, the lesson provides inspiration and entertainment, two things we should all have in our lives on a regular basis.

How Much Practice Time?

Do you need to practice more than once a week, for an hour, at your guitar lesson? You probably expect me to respond with a resounding, “Yes,” but I can’t because you don’t really need to. Should you? Absolutely, if you truly want to make any musical headway. But you don’t need to, and here is how I know.

Jim started taking guitar lessons with me in 2003. By 2008 he was an OK guitar player. That’s right, five years to become just OK. That is because Jim only played guitar at our lessons, one hour a week, and sometimes only three times a month. This was not something I had to question him about. He was honest and upfront. “I don’t have a lot of time to practice,” he said, “so is it OK if I just play here?” I realized that this was an odd situation and explained that he wouldn’t make any progress if he didn’t practice. He said he was fine with that. He just wanted to learn about guitar. I didn’t think we would last more than a month. By month three we were still reviewing the G chord, though we had added several more as well.

I realize a lot of teachers would not have stood for this sort of behavior, but I have learned over the years that my job as a teacher is not to impose my personal opinions about music and guitar playing (of which I have plenty) on students. Instead, my role is to give them what they want mixed with a little bit of what I think they need. Jim wanted to play guitar once a week, and I needed to teach him about music.

So, in addition to that relentless G chord treadmill, we also talked about what music is, what the guitar has to offer players and listeners, why I think the only Grateful Dead record anyone should own is Live Dead (Jim is huge Deadhead). And what did I learn? I learned that if you practice something once a week for an hour you can actually learn it in a few years. My regret? I wish I had started learning the piano at the same time and in the same way that Jim did the guitar. If so, I’d be a decent piano player by now! My point isn’t that I encourage you to take this approach, but that I have seen it work.

Playing vs. Practicing

There is a huge difference between playing and practicing. If you sound good when you are rehearsing, then you are not practicing, you are playing. Practicing means working on new material that challenges you; music that will not sound good at first. For beginners, this might mean picking up the tempo on your chord changes (Ex. 1). For intermediate players, you could try a couple of Mauro Giuliani’s 120 Studies for Right Hand Development (Ex. 2). An advanced guitarist should try practicing more chords than you would ever play in a real-life situation (Ex. 3), meaning this is impractical but fun. Let me break down each of these examples and show you how all of them can benefit guitarists at all levels.

Example 1 is one of the most ubiquitous chord progressions ever, used in literally thousands of songs (in varying orders, these four chords form the basis for songs as wide-ranging as “My Old School” by Steely Dan; “Nothing Else Matters” by Metallica; “The Passenger” by Iggy Pop; “Let it Be” by The Beatles; and countless folk and blues songs), with a slightly less common strumming pattern. The chords should be easy for most players; even beginners should start with these chords. But beginners and even some intermediate players will find the strumming pattern a challenge, as the four measures shown here contain four different combinations of strums! Novices should ignore the strum pattern for now. Four down strums per measure will work just fine. From there move to eight strums, down and up. Advanced players should test their rhythmic notation reading.

Examples 2a, 2b, 2c and 2d come from Mauro Giuliani’s right hand studies, which were first published in the early 19th century and have been utilized by the greatest fingerstyle players in the world for the past 200 years. The chords are all C moving to G7, but you should feel free to vary the chords to any you like; I suggest Am and Em as simple alternatives. Because this work is in the public domain, there are several sites on the Internet from which you can download all 120 exercises. I recommend a routine of practicing every fifth or sixth study, as they are grouped into similar patterns. Beginners can attempt these right hand patterns without fingering any chords; just use open strings (maybe try an opening tuning). Advanced guitarists are encouraged to challenge themselves with fast tempos and multiple chord changes.

Finally, Example 3 is an over-the-top variation on the progression known as “Rhythm Changes,” based on the Gershwin tune, “I Got Rhythm.” There is a chord change on every single beat! As mentioned, utilization of this is quite impractical, but it should be fun for players looking to push their chording ability to new levels. Beginners and intermediates should feel free to play only the first chord of each measure, for four beats.

Just Do It

Playing guitar does not have to be hard. It certainly presents challenges at first, but no more than any other new activity most people try…just don’t start with the F chord. Hopefully, if we ever meet at a party and I casually say to you, “I play guitar,” you can say, “So do I.”

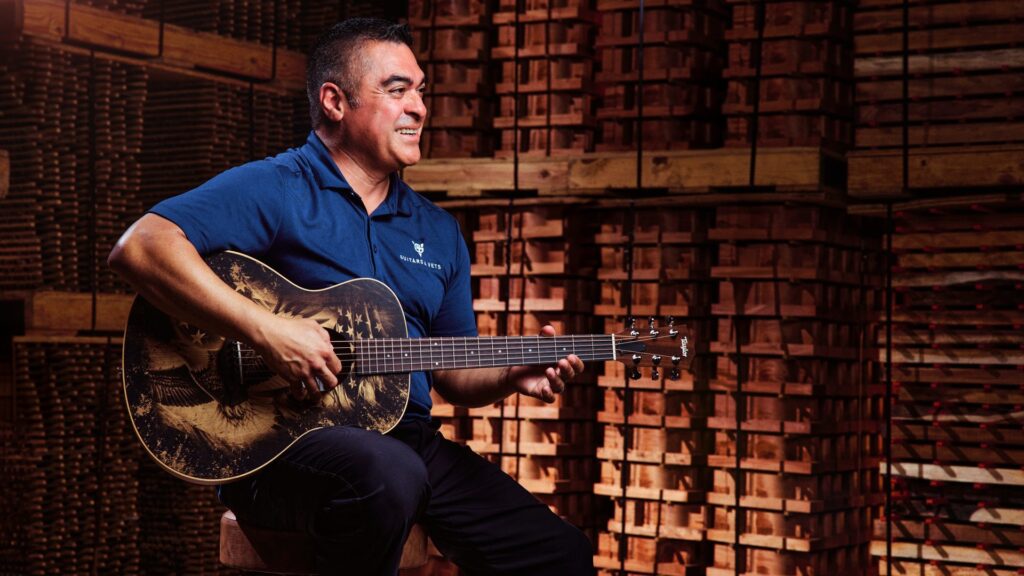

Shawn Persinger, a.k.a. Prester John, is a self-proclaimed “Modern/Primitive” guitarist who owns Taylor 410s and 310s. His latest sister CDs, Rise O’ Fainthearted Girls and Desire for a Straight Line (one instrumental, one vocal), with mandolinist David Miller, showcases a myriad of delightful musical paradoxes: complex but catchy; virtuosic yet affable; smart and whimsical. www.PersingerMusic.com